A global and increasingly complex food chain has created more opportunities for criminals to commit food fraud, writes Adam Maguire.

Most of us trust that the food and drink we buy is what it claims to be. We may occasionally scan the ingredients list, but what's listed there is taken at face value.

For the most part, we’re right to do so.

However there is a small chance that the products we pick up in our weekly shop are not what they claim to be – and telling the difference between real food and food fraud is no easy task.

What is Food Fraud?

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

It’s a very broad term – but in short it’s where food or drink is sold in a way that’s deceptive to the consumer. It’s usually part of an attempt to get more money from people than the product is actually worth.

In practice, though, that can mean a lot of things.

For example, it could involve a product pretending to be one thing when it’s actually another.

Or it could mean a product is diluted with a cheaper, inferior ingredient – one that is not declared that on the label.

It might be a product that claims to have a certain origin - like saying it’s made in Ireland when it’s actually been imported from somewhere else.

Or it could just be a straight up counterfeit – where a product is made to look like a branded version, when it’s actually not.

And there are lots of potential risks involved here – not least the fact that people could be paying over the odds for an inferior product.

Not to mention that they’re probably, ultimately, giving their money to criminals as part of the process.

Perhaps more concerning, though, are the other risks food fraud can create.

Because obviously when you have something in your food or drink that isn’t declared on the label, that could be a problem for people who exclude things from their diets for religious or ethical reasons.

It could also be a health risk, particularly for people who have allergies or intolerances.

And there have even been cases where toxic substances were added to food and drink – which has led to people getting seriously ill, and even dying.

So how big of a problem is it?

It’s estimated that fraudulent goods represent around 1% of the global food chain.

That sounds relatively small – but 1% globally would represent hundreds of millions of kilos of food each year.

It’s said that food fraud costs the global industry as much as $40 billion in lost value each year.

That’s in part because food fraud tends to be targeted towards the higher end of the industry – because that’s where there’s the biggest potential reward for fraudsters.

And it’s particularly common in product categories where there are both cheap and expensive options available – so think of the likes of wine, or olive oil.

But the cost to the industry is not just because there’s money spent on fraudulent food that would otherwise have gone to "genuine" products.

It’s also about the knock-on impact that fraud has on businesses and whole industries.

And Ireland has had its own high-profile experience with food fraud…

Yes – and it’s a good example of the wider impacts that food fraud can have.

Because while we’re now more than 10 years on from the horse meat scandal, parts of the industry here are still recovering from the reputational damage and the loss of trust.

The horse meat scandal came to light in early 2013, when the Food Safety Authority of Ireland revealed that it had identified horse meat in a range of products that were labelled as beef.

That included frozen beef burgers and some ready meals – which were labelled as beef-based, but some of which actually turned out to be 100% horse meat.

Some other samples were also found to have traces of pork in them.

And while it started here, it very quickly developed into a European scandal. Because the producers at the centre of the controversy would have supplied products to brands and retailers in the UK and other countries.

And once the FSAI raised the alarm, authorities in other countries conducted investigations of their own.

That ultimately identified a web of companies from all across the region that had processed, bought or sold contaminated meat. In the end it became clear that everything from retailers to hotels to care homes had been affected by the problem.

And this is a good example of how the costs of food fraud can quickly mount – because the horse meat scandal obviously led to the widespread recall of products from shops across Europe, there had to be a lot of money spent to notify consumers of what to do with the products they’d already bought.

And there was significant reputational damage done to the industry too.

It’s hard to quantify but there would have been people who were reluctant to return to affected brands even after supply chains had been 'cleaned’.

Not to mention the producers, who would have had to rebuild trust with the companies they supplied after the scandal.

What other examples of food fraud have there been?

Without wanting to downplay the seriousness of the horse meat scandal, it at least didn’t involve a major risk to public health. The same can’t be said of China’s baby formula scandal.

This was where a toxic chemical called melamine was added to the milk used in baby formula.

That was done because the milk in question had been watered down by producers who sought to make more money from the supply.

As it still had to pass quality control testing they added melamine, which would make it seem as though it had a higher protein content than was actually the case.

But melamine can cause kidney problems when consumed – including kidney stones and ultimately kidney failure.

And in the end Chinese authorities identified hundreds of thousands of babies and children that were affected by contaminated formula.

Tens of thousands of them ended up in hospital as a result of the melamine, and at least six deaths were connected to the fraud.

The impact of the fraud was also exacerbated by the fact that, when the problem first came to light, there was an attempt to downplay it.

Its discovery coincided with the Beijing Olympics and authorities did not want this moment of positive PR to be hindered by a scandal like this.

That meant that even when one producer – Sanlu - started a product recall, it wasn’t mentioned that it was due to potentially lethal contamination.

Ultimately it it took weeks before there was a wider investigation across the industry, which identified similar problems with other producers.

Outside of those specific cases, where else has food fraud been identified?

One other example of food fraud that’s been in the spotlight lately is around honey – and specifically the discovery that some so-called honey in fact contains cheaper sugar syrup.

Part of the problem here is how vague producers can be about the origins of the honey that’s in the jar or bottle.

At the moment you only have to say if the honey comes from within the EU or outside of it… and you’ll even find some labelled as being made up of ‘EU and non-EU sources’.

That means it could have come from anywhere in the world – so it’s essentially meaningless.

But there are now plans at an EU level to require more detail on the label about where the honey is coming from.

That includes having to name the top four countries of origin, along with the percentage of the honey that they represent.

There are also plans for better traceability from European bee-keepers.

Olive oil being another example of a product primed for fraud – because you of course have different qualities of olive oil, and very different price points attached.

Last year police in Spain and Italy seized 5,000 litres of olive oil as part of an investigation into an international gang that was buying low quality oil, and mixing it in such a way that they could pass it off as higher quality, extra virgin olive oil.

In some cases that might involve artificial colourings or flavourings being added – or it being mixed with other types of oil to give it the correct fat content.

And Italian authorities are clearly busy with this kind of thing, because just two weeks ago they made arrests relating to a counterfeit wine operation.

Again, this involved cheaper wine being sold as high-end stuff – in this case it was cheap Italian wine that was passed off as French wine worth up to €15,000 a bottle.

And the fraudsters had faked the labels and the wax seals and everything – doing such a good job that they were able to sell the bottles on to honest, upmarket wine traders around the world.

They, in turn, would have unwittingly sold the fraudulent wine on other customers.

But if you’re not buying expensive wine or olive oil, you’re probably okay?

Well, not necessarily.

Food fraud does tend to be in the high-end markets but, as we saw from the horse meat scandal, it can happen at any level.

Really as long as there’s money to be made by passing one thing off as another – or wherever it’s possible to dilute something down without the consumer noticing – then criminals will give it a go.

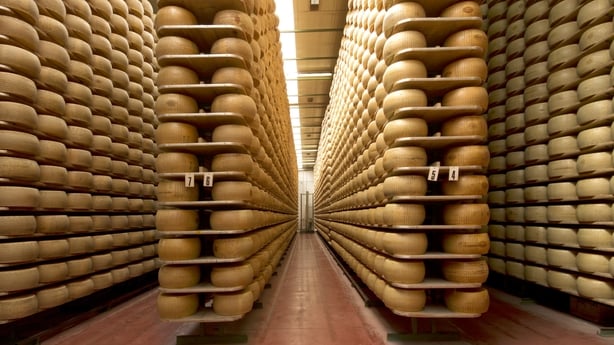

For example there was a case in the US where what was supposed to be parmesan cheese actually had as little as 2% parmesan - the rest being fillers and additives like cellulose (which is effectively wood pulp).

Parmesan cheese isn’t necessarily expensive to begin with – but obviously criminals felt there was a profit to be made by passing off a faked, diluted version. So they did it.

There have also been cases where herbs and spices have been mixed with other products – like flour, chalk, or even just cheaper herbs and spices. The same kinds of things have been found in ground coffee.

Meanwhile seafood is particularly vulnerable to fraud – because a lot of varieties of fish looks and even tastes very similar to one another.

That makes it’s relatively easy for a cheaper species to be mislabelled and sold off at a higher price.

So how is food fraud spotted?

The FSAI is the lead authority on this in Ireland – and it will conduct random testing on products to make sure that they are what they claim to be.

Producers would also be expected to keep a record of where they’re getting their ingredients from – and ideally you would be able to follow that line all the way back to the point of origin.

But that’s not always the case.

Because we know that the food industry is now global – and the supply chains involved are very complex and constantly changing.

You could have products where the raw ingredients are coming from countless suppliers dotted across Europe and even the world.

One of the positives to have come out of the horse meat scandal here was that it sparked greater cooperation between food safety authorities across Europe.

It led to the creation of the Agri-Food Fraud Network – which shares information and coordinates investigations to try to better deal with fraudsters.

Last year there was a 26% increase in notifications of suspicions of fraud – though some of that relates to the illegal trade of cats and dogs.

Of the actual food-related cases, there were investigations into things like the dilution of honey, and the passing off of cheap oil as an expensive alternative.

There were also investigations into the misleading labelling on meat, potential fraud relating to the forgery of food documentation and animal health certs, and suspected breaches of Europe’s Protected Denominations of Origin and Protection Geographical Indications regime.

That put rules on certain products that are deemed unique to an area or country - like Champagne, Parmesan, or Irish Whiskey.

Is there anything consumers can do to avoid it?

Unfortunately there’s probably no absolutely guaranteed way to avoid food fraud.

A good place to start is to stick to reputable retailers and well-known brands – but as we’ve seen from past experience, the reality is that they can be unwitting suppliers of problematic products.

In fact, even the producers themselves may not realise that what they’re using and selling on has issues – because the fraud was committed a number of steps back in the chain.

Really the best protection you can have is to look out for products that have an extra layer of traceability – those kinds of farm to fork schemes, like Bord Bia’s quality assurance programme.

And trying to shorten your supply chain by sticking to products that are grown and farmed in Ireland – or as a next-best, within the European Union – can help reduce your risk too.

The side benefit there being that you’re also reducing your food miles and shopping in a way that’s more sustainable in general.